FACTORY FOR THE FALLEN

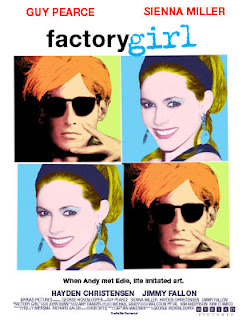

FACTORY GIRL (15)

reviewed by David Mahmoudieh at the UK premier

New York, 1965. If you were a hippie (and, hey, even if you weren’t) you may remember it as a time of Marx, Mahler and Mahatma Ghandi; of bell-bottoms, bra-burnings and boo; of Herman Hesse, crash-pads and driving around in beat-up Volkswagen vans with pink flowers painted on the side of them. It was the height of the swinging 60’s – and it had love, man. It also had Edie Sedgwick (Sienna Miller) and so is the setting for Factory Girl, a trepid and tragic tale of hedonistic overload amidst a race for the American dream that turned into a spiralling nightmare via the briefest of flirts with reality.

Less like watching a film and more like watching an accident waiting to and then eventually happen, Factory Girl inventively unfurls the meteoric rise and demise of Edie Sedgwick (Sienna Miller), a real-life 60’s female icon whose star blazed so bright it burnt out twice as fast. Such is the film’s quest for historical accuracy over contemporary chronicle, I feel better compelled to first summarize Sedgwick’s celebrity as it was rather than as it is here foretold.

On the face of it Sedgwick was adored as the hip-hype silver-mini-skirt wearing darling of America; fascinatingly beautiful, charismatic and full of zest. That was, until she crossed paths with Andy Warhol, the anti-enfant terrible of fashionable non-cinema with his breed of eccentric, and by his own admission, meaningless films which somehow inspired an entire generation to extrapolate all manner of meaning from them. Warhol proved to be the beginning of the end for Sedgwick, as an alluring new World opened up before her; one besieged within the upper circles of a neo-artistry era which was a perpetual eruption of sex, drugs, rock, roll and Sedgwick's speciality – urbanite fashion. Eventually becoming an actress, her short-lived but fast-spent life became legend when a diet of amphetamines and vodka lead her to a fatal drug’s overdose in 1971.

Alas, back with the times and similar to the Warhol of yesteryear, the Warhol depicted on-screen (Guy Pearce) sees promise in Sedgwick’s raw and vivacious vulnerability and quickly introduces her to his wild world of ‘The Factory’ – a rundown industrial unit he's malformed into a bohemian paradise. This rag-tag mix of musicians, poets, artists and actors do little more than craft outré-artistic expressionistic films by day before throwing glam, drug-drenched parties by night.

As always, stories riddled with this much ravishment and declension remain compulsively watch-able solely for what they are and don’t need to be told in complex terms. So credit director George Hickenlooper who has added a hint of sophistication to a simple narrative, keeping the film nourished with the power of understatement and cinematic delicacy. What’s refreshingly unusual is that Factory Girl isn’t trying to pass judgment – rather just tell the story as it happened, not as we’d like to think it did.

Equally, Hickenlooper’s casting skills seem similarly adept, with Sienna Miller the obvious choice for the title role: just like her character, Miller first found fame through a brace of failed relationships with celebrity boyfriends only to now herself these days trying to find her feet as an actress.

And special mention to Hayden Christensen (Star Wars) as Warhol’s love-rival, Billy Quinn (who despite the ‘purely coincidental’ disclaimer is clearly meant to be Bob Dylan). Christensen delivers an inch-perfect portrayal of a character he can’t for legal reasons play too obviously but still manages to exemplify with sufficient familiarity.

The character of Quinn appears to offer Edie a way out of Warhol’s addictive World and straight into another, but the sincerity of their romance is not all as it seems. You wouldn’t think it...

Despite the merit of the eerily convincing performances on show, the film looks certain to become most famous for its steamy and controversial love scenes, in which Miller and her co-star Christensen (who dated for while during and after filming) are reported to have performed the scenes for real.

(Sienna Miller last night at the film's London premier)

Whether that’s true or not, and as persuasive as the scene is, it functions only as extravagant ballast, almost pinning the audience’s attentions down and away from the more interesting things happening on the film's periphery.

Factory Girl has much greater lessons on life to offer us than the potential lowly depths of modern acting habits, and first-and-foremost serves as an insight into the actions of a somewhat forgotten princess of pop-couture that can be both abhorred and yet, at the same time, tragically admired.

As for the controversy and critical storm that is certain to rain upon the film's unavoidably flagship scene, I'm sure Edie wouldn't have wanted it any other way.

© David Mahmoudieh 2007

FACTORY GIRL (15)

reviewed by David Mahmoudieh at the UK premier

New York, 1965. If you were a hippie (and, hey, even if you weren’t) you may remember it as a time of Marx, Mahler and Mahatma Ghandi; of bell-bottoms, bra-burnings and boo; of Herman Hesse, crash-pads and driving around in beat-up Volkswagen vans with pink flowers painted on the side of them. It was the height of the swinging 60’s – and it had love, man. It also had Edie Sedgwick (Sienna Miller) and so is the setting for Factory Girl, a trepid and tragic tale of hedonistic overload amidst a race for the American dream that turned into a spiralling nightmare via the briefest of flirts with reality.

Less like watching a film and more like watching an accident waiting to and then eventually happen, Factory Girl inventively unfurls the meteoric rise and demise of Edie Sedgwick (Sienna Miller), a real-life 60’s female icon whose star blazed so bright it burnt out twice as fast. Such is the film’s quest for historical accuracy over contemporary chronicle, I feel better compelled to first summarize Sedgwick’s celebrity as it was rather than as it is here foretold.

On the face of it Sedgwick was adored as the hip-hype silver-mini-skirt wearing darling of America; fascinatingly beautiful, charismatic and full of zest. That was, until she crossed paths with Andy Warhol, the anti-enfant terrible of fashionable non-cinema with his breed of eccentric, and by his own admission, meaningless films which somehow inspired an entire generation to extrapolate all manner of meaning from them. Warhol proved to be the beginning of the end for Sedgwick, as an alluring new World opened up before her; one besieged within the upper circles of a neo-artistry era which was a perpetual eruption of sex, drugs, rock, roll and Sedgwick's speciality – urbanite fashion. Eventually becoming an actress, her short-lived but fast-spent life became legend when a diet of amphetamines and vodka lead her to a fatal drug’s overdose in 1971.

Alas, back with the times and similar to the Warhol of yesteryear, the Warhol depicted on-screen (Guy Pearce) sees promise in Sedgwick’s raw and vivacious vulnerability and quickly introduces her to his wild world of ‘The Factory’ – a rundown industrial unit he's malformed into a bohemian paradise. This rag-tag mix of musicians, poets, artists and actors do little more than craft outré-artistic expressionistic films by day before throwing glam, drug-drenched parties by night.

As always, stories riddled with this much ravishment and declension remain compulsively watch-able solely for what they are and don’t need to be told in complex terms. So credit director George Hickenlooper who has added a hint of sophistication to a simple narrative, keeping the film nourished with the power of understatement and cinematic delicacy. What’s refreshingly unusual is that Factory Girl isn’t trying to pass judgment – rather just tell the story as it happened, not as we’d like to think it did.

Equally, Hickenlooper’s casting skills seem similarly adept, with Sienna Miller the obvious choice for the title role: just like her character, Miller first found fame through a brace of failed relationships with celebrity boyfriends only to now herself these days trying to find her feet as an actress.

And special mention to Hayden Christensen (Star Wars) as Warhol’s love-rival, Billy Quinn (who despite the ‘purely coincidental’ disclaimer is clearly meant to be Bob Dylan). Christensen delivers an inch-perfect portrayal of a character he can’t for legal reasons play too obviously but still manages to exemplify with sufficient familiarity.

The character of Quinn appears to offer Edie a way out of Warhol’s addictive World and straight into another, but the sincerity of their romance is not all as it seems. You wouldn’t think it...

Despite the merit of the eerily convincing performances on show, the film looks certain to become most famous for its steamy and controversial love scenes, in which Miller and her co-star Christensen (who dated for while during and after filming) are reported to have performed the scenes for real.

(Sienna Miller last night at the film's London premier)

Whether that’s true or not, and as persuasive as the scene is, it functions only as extravagant ballast, almost pinning the audience’s attentions down and away from the more interesting things happening on the film's periphery.

Factory Girl has much greater lessons on life to offer us than the potential lowly depths of modern acting habits, and first-and-foremost serves as an insight into the actions of a somewhat forgotten princess of pop-couture that can be both abhorred and yet, at the same time, tragically admired.

As for the controversy and critical storm that is certain to rain upon the film's unavoidably flagship scene, I'm sure Edie wouldn't have wanted it any other way.

© David Mahmoudieh 2007

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home