Merci, Zizou

by David Mahmoudieh

Can the World really begrudge a man who gave us a whole new interpretation of the beautiful game?

He was a legend whose name was spoke with gasps and veneration; with idol worship and exaltation; whose very mention lit up eyes and lifted brows of football lovers the world over.

He was a hero to the masses, a man of the people, champion of all who knew or ever played alongside him. And on July 9th 2006, in what was meant to be his valedictory swang-song, Zinedine Zidane captained his nation into the World Cup final in Germany as France’s first man on the pitch... and as history has since so cruelly told us was all too prematurely the first one off it.

(Final Strike: Zidane's last goal of his career, scored

in a World Cup final)

A great deal has since been all but said and done with regards what happened in Berlin on what proved to be a fateful night for the greatest player of his generation and his last ever march into battle.

Three months on, and the World Cup withdrawal syndrome blues befall the cobbled streets of Rome, the scene of a victory parade that saw an Italian community indulging in the grandest celebrations for a triumph achieved via the narrowest of margins. But now that the stardust has settled, even the most begrudging of Italian patriots can’t deny the gaping void felt by the permanent departure of the wizard that was Zinédine Zidane.

As a veteran of three World Cups, and one of only two players to win the World Player of the Year Award three times, Zidane has claimed the scalp of every top honour that the game has to offer. But through football Zidane won so much more than just trophies.

(World's Apart: Zidane's two goals in the 1998

final earned France their first World Cup trophy)

Born on June 23 1972, Zinédine Yazid Zidane grew up on a council estate in the rough, tough, impoverished back-streets of Marseille, France. He spent a modest childhood perfecting his skills amidst ghetto streets engulfed with violence, more so with him being the son Algerian immigrant parents; an abhorently difficult upbringing which fine-tuned his inherent rage to be the best in whatever field he chose to excel in. Yet despite a journey which has taken him to the highest echelons of football’s elite, Zidane was raised and remains to this day a man who never forgot his roots.

(Zidane and team-mate Patrick Vieira embrace

after Zizou's superb goal against Spain)

The man nicknamed ‘Zizou’ endured a pertinent love-affair with a more recently disgraced Juventus, spear-heading the Old Lady’s charge to three Serie A titles (no bungs required) and two champions league finals during his five years at the club.

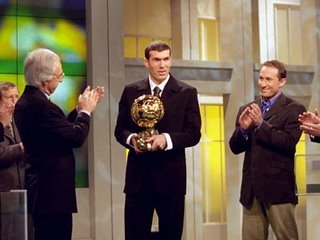

(Zidane receiving his first World Player of the Year

Award; he would go on to win two more)

Juventus have a fine tradition with Frenchman; Platini, who wore the famous black and white, then (and now manager) Didier Deschamps, who won the fans over with his combative and gladatorial style, not to mention Trezeguet, Henry, Vieira, Thuram - all of whom have given service to Italy's most famous club.

And it was here, in 1996, that fans first started to admire their newest Frenchman for his decorum as much as his skills with a football; particularly club president Gianni Agnelli, who in addition to being bedazzled by Zidane's technical brilliance was baffled by his unwillingness to take advantage of the many rewards freely tendered to him by the club; women, nightclubs, cars.

(Razu and Zizou: Lizarauz mobs Zidane after scoring a

dramatic late free-kick against England at Euro 2004)

A far cry from his fellow ‘professionals’, Zizou has always remained a model ambassador for the game, inscrutably focused on his career and impeccably devoted to his wife and four Italian-named sons (an acknowledgement by Zidane to the country they were living in at the time of their births).

The point, Zidane united a bond between him and the Italian people long before his confrontation with Materazzi, and one isolated incident can never break that.

(Higher Power: some attribute Zidane's humble nature

and tranquillity to his faith in religion and a higher cause)

Perhaps that, above all, is Zidane’s greatest gift to the World; how a man’s unanimous popularity somehow transcends all racial, religious and cultural divides in the ever-heightening tension of a multi-ethnic Europe.

(ZZ Clause: Zidane visits a sick child as part of his work

with various charities, including the UNDP)

As for his footballing eminence, Zidane is already a resident great in the halls of FIFA fame, and his retirement has re-ignited the fires of an almost universal debate that Zidane succeeds the incumbent Pele/Maradona fusion as THE out-and-out greatest player of all time. There’s certainly a strong case for it. Zizou won treble the amount of honours earned by Maradona, played at a much more significant club level than Pelé and was the key part of a French side that became the only team in history to win the World Cup and European Championships back-to-back.

(Rare Sight: Zidane helped France become the only

country in history to hold international football's

two most prestigious trophies at the same time)

Yet in spite of his other-worldly gift for the game and his humbling personality in private, the debate will no doubt be forever raging as to whether his antics on a football pitch following Materazzi's comments on his prom-night of the game were wholly inexcusable. Though, in his defence, people have been head-butted in the street for saying far less.

(L'Incredible Zizou: need I say more...?)

I’m sure Zidane, in years to come, will look back on his exit from a sport he gave so much to with a patent repent for the manner in which he left it, but maybe he got the better end of the deal. Unless Italy launch a historically unlikely resistance to their crown (only twice has the trophy been retained by its victors), come July 2010 the cup will be heading somewhere else. But Zidane’s legend will last far longer than four years.

His career may have ended, his legacy has just begun...

© David Mahmoudieh 2006

by David Mahmoudieh

Can the World really begrudge a man who gave us a whole new interpretation of the beautiful game?

He was a legend whose name was spoke with gasps and veneration; with idol worship and exaltation; whose very mention lit up eyes and lifted brows of football lovers the world over.

He was a hero to the masses, a man of the people, champion of all who knew or ever played alongside him. And on July 9th 2006, in what was meant to be his valedictory swang-song, Zinedine Zidane captained his nation into the World Cup final in Germany as France’s first man on the pitch... and as history has since so cruelly told us was all too prematurely the first one off it.

(Final Strike: Zidane's last goal of his career, scored

in a World Cup final)

A great deal has since been all but said and done with regards what happened in Berlin on what proved to be a fateful night for the greatest player of his generation and his last ever march into battle.

Three months on, and the World Cup withdrawal syndrome blues befall the cobbled streets of Rome, the scene of a victory parade that saw an Italian community indulging in the grandest celebrations for a triumph achieved via the narrowest of margins. But now that the stardust has settled, even the most begrudging of Italian patriots can’t deny the gaping void felt by the permanent departure of the wizard that was Zinédine Zidane.

As a veteran of three World Cups, and one of only two players to win the World Player of the Year Award three times, Zidane has claimed the scalp of every top honour that the game has to offer. But through football Zidane won so much more than just trophies.

(World's Apart: Zidane's two goals in the 1998

final earned France their first World Cup trophy)

Born on June 23 1972, Zinédine Yazid Zidane grew up on a council estate in the rough, tough, impoverished back-streets of Marseille, France. He spent a modest childhood perfecting his skills amidst ghetto streets engulfed with violence, more so with him being the son Algerian immigrant parents; an abhorently difficult upbringing which fine-tuned his inherent rage to be the best in whatever field he chose to excel in. Yet despite a journey which has taken him to the highest echelons of football’s elite, Zidane was raised and remains to this day a man who never forgot his roots.

(Zidane and team-mate Patrick Vieira embrace

after Zizou's superb goal against Spain)

A natural leader, both on and off the field, his passage from poverty to prominence has since become an inspiration for disadvantaged children not just in France, but the World over. And irrespective of his infamous confrontation with a certain Marco Materazzi, Zidane is far from considered an enemy of the Italian game and people.

The man nicknamed ‘Zizou’ endured a pertinent love-affair with a more recently disgraced Juventus, spear-heading the Old Lady’s charge to three Serie A titles (no bungs required) and two champions league finals during his five years at the club.

(Zidane receiving his first World Player of the Year

Award; he would go on to win two more)

Juventus have a fine tradition with Frenchman; Platini, who wore the famous black and white, then (and now manager) Didier Deschamps, who won the fans over with his combative and gladatorial style, not to mention Trezeguet, Henry, Vieira, Thuram - all of whom have given service to Italy's most famous club.

And it was here, in 1996, that fans first started to admire their newest Frenchman for his decorum as much as his skills with a football; particularly club president Gianni Agnelli, who in addition to being bedazzled by Zidane's technical brilliance was baffled by his unwillingness to take advantage of the many rewards freely tendered to him by the club; women, nightclubs, cars.

(Razu and Zizou: Lizarauz mobs Zidane after scoring a

dramatic late free-kick against England at Euro 2004)

A far cry from his fellow ‘professionals’, Zizou has always remained a model ambassador for the game, inscrutably focused on his career and impeccably devoted to his wife and four Italian-named sons (an acknowledgement by Zidane to the country they were living in at the time of their births).

The point, Zidane united a bond between him and the Italian people long before his confrontation with Materazzi, and one isolated incident can never break that.

(Higher Power: some attribute Zidane's humble nature

and tranquillity to his faith in religion and a higher cause)

Sporting feats aside, there’s an entirely more serious achievement that needs to be recognised here: one which underlines a certain irony when you consider that not fifty years ago it would have been inconceivable that a half-Algerian who describes himself as a ‘non-practising Muslim’ would not only have his face projected atop Paris's Arc de Triomphe bearing the banner "Zizou President", but also be officially labelled the 'most popular Frenchman of all time'.

Perhaps that, above all, is Zidane’s greatest gift to the World; how a man’s unanimous popularity somehow transcends all racial, religious and cultural divides in the ever-heightening tension of a multi-ethnic Europe.

(ZZ Clause: Zidane visits a sick child as part of his work

with various charities, including the UNDP)

As for his footballing eminence, Zidane is already a resident great in the halls of FIFA fame, and his retirement has re-ignited the fires of an almost universal debate that Zidane succeeds the incumbent Pele/Maradona fusion as THE out-and-out greatest player of all time. There’s certainly a strong case for it. Zizou won treble the amount of honours earned by Maradona, played at a much more significant club level than Pelé and was the key part of a French side that became the only team in history to win the World Cup and European Championships back-to-back.

(Rare Sight: Zidane helped France become the only

country in history to hold international football's

two most prestigious trophies at the same time)

What's more, few players have graced the sport with such an original talent - or any other sport for that matter, and to survive at the top of the modern game for more than a decade in this most ruthless age of football where more than double the number of games are played per season compared to Pele or Maradona's era of twenty years ago, is a testament to an irreplaceable footballing myth.

Yet in spite of his other-worldly gift for the game and his humbling personality in private, the debate will no doubt be forever raging as to whether his antics on a football pitch following Materazzi's comments on his prom-night of the game were wholly inexcusable. Though, in his defence, people have been head-butted in the street for saying far less.

(L'Incredible Zizou: need I say more...?)

I’m sure Zidane, in years to come, will look back on his exit from a sport he gave so much to with a patent repent for the manner in which he left it, but maybe he got the better end of the deal. Unless Italy launch a historically unlikely resistance to their crown (only twice has the trophy been retained by its victors), come July 2010 the cup will be heading somewhere else. But Zidane’s legend will last far longer than four years.

His career may have ended, his legacy has just begun...

© David Mahmoudieh 2006