Ooh la la, it’s the Cannes Cannes

The Magic of the Cannes Film Festival

reviewed by David Mahmoudieh

For a fortnight each May, thousands of producers, directors, writers, actors and ‘patrons’ invade the quiet, nonchalant town of Cannes; a peaceful summer resort on the French Riviera, overrun with the responsibility of staging the most famous and prestigious film festival in the world.

A greatly publicised yet private affair, The Cannes Film Festival is the ultimate networking arena reserved for industry professionals to annually convene for business, pleasure – and parties.

Originally set up in 1939, the festival was designed to serve as a platform where films could be shown completely without bias or political censorship, and it prides itself on selecting fresh, innovative, pioneering films before serving them on a platter to critics and distributors alike to devour or develop a taste for accordingly.

The truth of the matter is that controversy sells big at Cannes, with the organisers almost deliberately counter-balancing quality with an intent to showcase and officially endorse the kind of revolutionary cinema other festivals would simply dare not entertain.

Of course, no film’s press kit is quite complete without the lampoon of a red carpet premiere and so by nightfall the tuxedos come out for the evening Grand Theatre Lumiere, with the odd sighting of P Diddy or Hugh Hefner and his Playboy Bunnies, kindly donating their forearms for Zimmer frames.

Typically, premieres are held between three and four times a day, each one preceded by a gaudy procession on the Red Carpet; a ‘pageant’, if you will, of carefully orchestrated affairs in which the producers, directors, actors/actresses and their endless entourages are paraded before the press prior to taking up their seats in the same screening and awaiting a reaction.

And it is here, beneath the facade of majestic camaraderie, that a more brutal process separates what gets remembered from the fast forgotten.

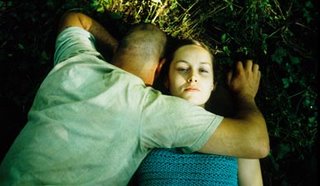

(Audrey Tatou at her press call for the Da Vinci

Code, an out-of-competition entry at the festival)

There’s no denying it, there’s a great pseudo-Roman Empire quality about Cannes; a do-or-die Masonic white-ball/black-ball mindset surrounding every screening. Not least during those priceless, anxious few seconds of silence when a viewing finishes and the credits roll – the filmmakers gulping hard, awaiting either the thumbs up or thumbs down from the notoriously unrelenting crowd – usually in the form of rhythmic clapping or erratic and untamed boos. After all, these are my fellow French.

More than 1,500 films from over 100 countries put themselves up for the scrutiny of the hand-selected international jury (this year including Chinese director Wong Kar Wai and Samuel L Jackson), with only a very limited number of places within the official selection categories; Feature Films, Shorts, and First/Second-Time Directors. But as well as film-makers flaunting their ingenuity – the buzzword on everyone’s lips is ‘distribution’.

Every film to hit a cinema has an often unappreciated yet intense distribution cycle behind it (i . e . once the film has been made a distributor will either buy it and take on the complete distribution liability or work in conjunction with the production house in delivery of the film to a geographically pre-targeted circulation).

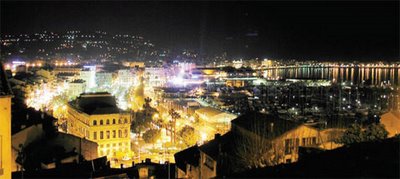

(Cannes by night)

Large-scale films like Da Vinci Code or X-Men 3, for example, obviously have provisional distribution in place before a single reel of film has passed through the camera. However, the smaller, independent productions which rely on self-funding or private investment often take the plunge and financial risk with the confidence (and balls, it must be said) that they’ll end up with an end product so great that someone, somewhere, will surely want to distribute it. Not – as most learn – always the case.

Thus, behind the glamorous exterior and ritzy premieres, located deep in the heart of the main Palais Des Festival, lies the Marche Du Film; a trade-floor of the film industry, where dreams and nightmares are both made and mauled, where suits dash around trying to fulfil an impossible roster of meetings within endless corridors of walls lathered in posters for appallingly-named films you’ve never even heard of, starring talent you thought would know better.

The Magic of the Cannes Film Festival

reviewed by David Mahmoudieh

For a fortnight each May, thousands of producers, directors, writers, actors and ‘patrons’ invade the quiet, nonchalant town of Cannes; a peaceful summer resort on the French Riviera, overrun with the responsibility of staging the most famous and prestigious film festival in the world.

A greatly publicised yet private affair, The Cannes Film Festival is the ultimate networking arena reserved for industry professionals to annually convene for business, pleasure – and parties.

Originally set up in 1939, the festival was designed to serve as a platform where films could be shown completely without bias or political censorship, and it prides itself on selecting fresh, innovative, pioneering films before serving them on a platter to critics and distributors alike to devour or develop a taste for accordingly.

The truth of the matter is that controversy sells big at Cannes, with the organisers almost deliberately counter-balancing quality with an intent to showcase and officially endorse the kind of revolutionary cinema other festivals would simply dare not entertain.

Of course, no film’s press kit is quite complete without the lampoon of a red carpet premiere and so by nightfall the tuxedos come out for the evening Grand Theatre Lumiere, with the odd sighting of P Diddy or Hugh Hefner and his Playboy Bunnies, kindly donating their forearms for Zimmer frames.

Typically, premieres are held between three and four times a day, each one preceded by a gaudy procession on the Red Carpet; a ‘pageant’, if you will, of carefully orchestrated affairs in which the producers, directors, actors/actresses and their endless entourages are paraded before the press prior to taking up their seats in the same screening and awaiting a reaction.

And it is here, beneath the facade of majestic camaraderie, that a more brutal process separates what gets remembered from the fast forgotten.

(Audrey Tatou at her press call for the Da Vinci

Code, an out-of-competition entry at the festival)

There’s no denying it, there’s a great pseudo-Roman Empire quality about Cannes; a do-or-die Masonic white-ball/black-ball mindset surrounding every screening. Not least during those priceless, anxious few seconds of silence when a viewing finishes and the credits roll – the filmmakers gulping hard, awaiting either the thumbs up or thumbs down from the notoriously unrelenting crowd – usually in the form of rhythmic clapping or erratic and untamed boos. After all, these are my fellow French.

More than 1,500 films from over 100 countries put themselves up for the scrutiny of the hand-selected international jury (this year including Chinese director Wong Kar Wai and Samuel L Jackson), with only a very limited number of places within the official selection categories; Feature Films, Shorts, and First/Second-Time Directors. But as well as film-makers flaunting their ingenuity – the buzzword on everyone’s lips is ‘distribution’.

Every film to hit a cinema has an often unappreciated yet intense distribution cycle behind it (i . e . once the film has been made a distributor will either buy it and take on the complete distribution liability or work in conjunction with the production house in delivery of the film to a geographically pre-targeted circulation).

(Cannes by night)

Large-scale films like Da Vinci Code or X-Men 3, for example, obviously have provisional distribution in place before a single reel of film has passed through the camera. However, the smaller, independent productions which rely on self-funding or private investment often take the plunge and financial risk with the confidence (and balls, it must be said) that they’ll end up with an end product so great that someone, somewhere, will surely want to distribute it. Not – as most learn – always the case.

Thus, behind the glamorous exterior and ritzy premieres, located deep in the heart of the main Palais Des Festival, lies the Marche Du Film; a trade-floor of the film industry, where dreams and nightmares are both made and mauled, where suits dash around trying to fulfil an impossible roster of meetings within endless corridors of walls lathered in posters for appallingly-named films you’ve never even heard of, starring talent you thought would know better.

A SHEEP AMIDST THE WOLVES

My own artistic agendas lay somewhere between marvelling at the splendour of what was on show as a critic and, as a filmmaker, the development of a large-budget short and a feature. Not sure 'fun' is the right word to describe the experience of juggling the two.

Meetings that clashed with screenings. Deadlines that clashed with pitches. And to top it all off, temperatures so high they should be illegal.

It was my fourth time at the festival, so I knew what I was letting myself in for. As too did my collaborator, Rob, who as producer had the interconnective burden of fingers in production pies other than my own.

Our first meeting as a pair came in that flurry of activity that is the Marche Du Film with an American distributor, an encounter which extinguished any doubts either of us may have had that this was gonna be anything other than one loooooong festival...

I won't name the production company or (according to his card) the 'Head of Acquisitions' we had the delight of sharing a wonky round-table with, but I'm sure the words 'blood' and 'stone' won't give too much away.

(Wheelers and dealers of the film World unite in the Marche Du Film)

We arrive well within time, their stand looks okay, they look professional. The posters on the wall aren't too convincing, but never judge a book and all that. We're pitching one of my screenplays, a hi-concept character drama about human trafficking and as we're readying our case our contact finishes up his previous meeting that's now slightly over-ran. Hey, he's obviously in demand so far, so good.

Finally we sit down and start talking. The guy's very friendly - he looks a bit like Robert Forster in Jackie Brown... until I put my glasses on -- and hell, he looks a lot like Robert Forster in Jackie Brown!! Rob (producer, not the lookalike) kicks things off and I'm sitting there wondering whether our host's gonna break out with The Delfonics' "Didn't I Blow Your Mind", seen as he keeps nodding his head in small, rhythmic circles while we're pitching. We finish what we've got to say; it was sharp, concise, to the point - we didn't do too bad. And then...?

Well then he stops nodding and looks at us deadpan, and I betray you not, says with all the blank sincerity I've ever seen in any man, woman or child,

"Does it have a creature in it?"

???????

Er.... yeah... of course it does, mate. And the bloody abonimal snowman, too. I mean, why wouldn't it; it's not horror, it's not sci-fi, it's not Donnie Darko - but, now that you mention it, yes, let's put a big bludgeoning beastie in there – why oh why didn’t I think of that before???!

Needless to say I lost interest immediately. And when I further compounded his devestation with the miserable news that there was no room for Swamp Thing, The Creature from the Black Lagoon or any other cheap, blood-lusting animatronic novelty for that matter - thankfully - so did he.

Excuse ourselves we did, albeit a little more politely.

As a baffled Rob and I are trying to come to terms with the trauma of what we've both just been through, and the seemingly undeniable existence of such mundane, narrow-minded beings at so enchanting and forward-thinking a place, our blind discussions are sightlessly leading us through the analogous maze of boothes and into the jaws of the kind of critter that would be greeted with glee by our previous serpent-seeking accommodator.

It finally dawns on us we're somewhat off track when we arrive at the abovementioned cretin's stall and find ourselves being ushered in by a marketing girl of some middle-tier distributor to watch some preceptibly deplorable film about a giant lizard terrorizing the streets of New York. A giant lizard, eh? Well, I've never seen that before.

Here in the oversized, cul-de-sac boothe we eventually stumble upon a delightful know-it-all (again, no names, don't fancy being sued) who before we can open our mouths and ask for directions back to the real World barks that he doesn't read scripts until they're at the 15th draft. Grrrrriiight. All fellow creative writers finished breaking your knuckles on the monitor-glass? Well get this - in his own golden words, he wouldn't even show an 8th draft to his dog. Wow. That's one picky dog.

For any Cannes virgins now frigid with the ruminations of their 'first time', don't let my pleasant misfortunes lead you to festival celibacy. Cannes, and particularly the Marche Du Film, on any other day offers filmmakers and producers a grand networkng arena. And to be fair, if you look in the right places you'll find the right people. Just where those people and places are is the art of this grand old lark, I'm afraid - but rest assured, I'll let you know when I find them....

In the end myself and Rob deduced that for now we were much better off with the contacts we already had in the UK, though we did hear rumours of some Hollywood-defiant Europeans floating around who would actually entertain the idea of investing in something without a monster in it.

Guess that means this here sucker'll be joining the hunt again next year then, huh?

Ah, life’s a pitch.

© David Mahmoudieh 2006